One of my favorite places to go on the Big Island of Hawaii is a sacred historic site called “The Place of Refuge,” or in Hawaiian, Pu’uhonua. You’ll find out more information about this national historic park in my blog about it elsewhere on this website.

The last time I visited Pu’uhonua, I paid more attention to the plant that was growing abundantly in the back half of the compound – the section where those individuals who managed to swim to safety and cross the black lava and sand beach lived in safety until they were declared forgiven and free to return to normal life. I showed the park ranger the pictures I had taken and she identified it as Naupaka, a plant native to the Hawaiian Islands, although similar varieties are found on all subtropical Pacific and Indian ocean coasts.

There are actually two varieties of Naupaka which grow in Hawaii. Naupaka Kuahiwi, also known as mountain Naupaka, grows at the higher elevations of the islands, usually above 150 feet. In contrast, Naupaka Kahakai or coastal Naupaka grows from sea level to about 150 feet in elevation. The mountain Naupaka has purple fruits or berries which can be used to make purple dye, while the mountain Naupaka has green and white fruits (sometimes with purple streaks) which make cream colored or greenish dye.

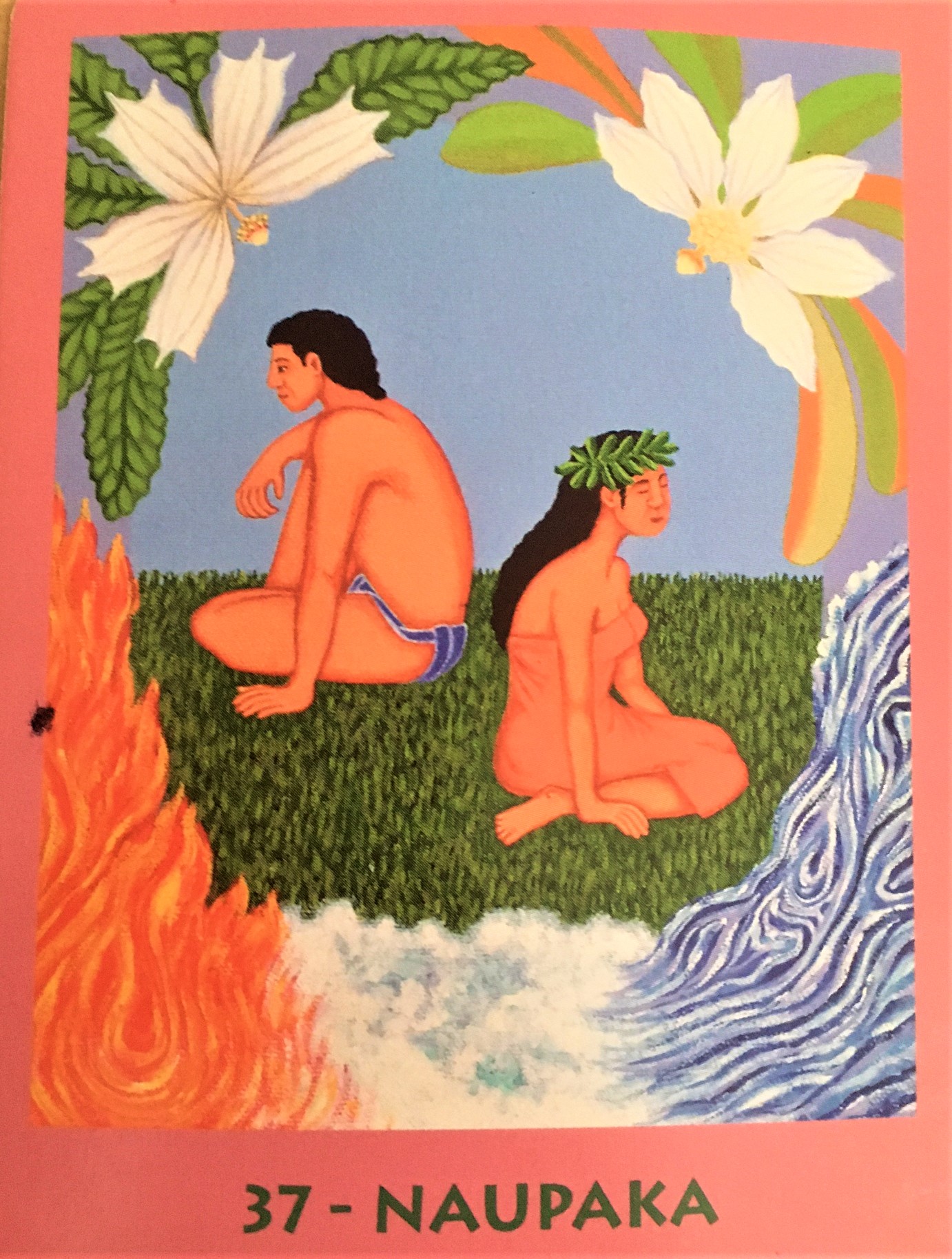

The blossoms on both varieties of Naupaka are half blossoms, but they face in opposite directions to the center. If you join the flowers from both species together, they make a whole flower – which is, of course, the stuff of legends.

It seems that in the distant past, a young princess named Naupaka fell in love with a commoner named Kaui. The rules at that time forbid marriage between the ali’i (royalty) and commoners. There are many variations concerning the specific events which followed. In one version, Naupaka and Kaui sought guidance from a priest at a heiau or temple, but he couldn’t find a solution. Finally, in despair, Naupaka tore the white flower she was wearing in her hair in half and gave one part to Kaui. “You go to live by the sea, and I will stay in the mountains” – and so the two lovers parted sadly and permanently. The Naupaka plants were so saddened by the lovers’ tears that they began to bloom with just half a flower.

In another rendition, the lovers were called Momi (pearl) and Ikaika (man of strength). They loved each other so much that one felt incomplete without the other. Madame Pele was jealous of their devotion and banished Momi to the mountains and Ikaika to the sea. There are also versions where the lovers had a fight and separated or where she was unfaithful when he was away fighting in a battle and that caused the breakup. Regardless of the story, the outcome is always the same — permanent separation with the woman staying in the mountainous area and the man living near the sea.

Despite how it came about, there is no doubt the two varieties of Naupaka plants are similar but different. My pictures are of coastal Naupaka, which is the only indigenous Naupaka with green and white berries. All other Naupaka in Hawaii have the purple or dark colored fruits.

Coastal Naupaka is a hardy shrub, whereas the mountain variety grows as either a tree or a shrub. At Pu’uhonua, coastal Naupaka grows quite thickly in the sandy, volcanic soil and can stretch upward as high as fifteen feet. It is extremely drought, heat, and salt tolerant, able to survive right next to the ocean. Its mountain “twin,” on the other hand, doesn’t deal well with either heat or salt and needs a lot of water.

The leaves on the coastal Naupaka are smooth-edged and range from light to medium green. Sometimes there are short hairs on the stems. The mountain variety has darker green leaves with toothed margins. In both plants, however, the leaves are moderately succulent, meaning they retain water.

The flowers of both species of Naupaka are tiny, cream or white with a greenish tinge. In agreement with the legend, each has only half a flower; the bottom half in the coastal version and the top half in the mountain variety. This unique trait led to the generic name of the species which is Scaevola, meaning “left-handed” or “awkward” – sadly, a still existing remnant of past historical discrimination against left-handedness in particular and being different in general.

The white fruit of the coastal Naupaka is impervious to sea water and will float in the ocean looking for a new place to grow. However, once they reach promising soil, they must have fresh water in order to germinate.

In addition to making dyes, native Hawaiians used the flowers, leaves and berries in lei making. The white berries and the root bark of the coastal Naupaka were mixed with salt and used for cuts and wounds, while in other lands, the leaves of the plant were steamed and eaten as greens.

Have any thoughts about which version of the legend is true? When I stood amidst the plants at the Place of Refuge, I was swayed into believing that indeed a commoner had fallen in love with an ali’i. The Ali’i were not just royalty but were believed to have been descended from the Gods. As such, they were highly protected and a commoner who dared to love a princess could probably have received a death sentence. The only way to avoid such a punishment was to swim to a place of refuge and ask forgiveness of the priests there. So, perhaps, when he and Naupaka separated, Kaui did just that. He and his half flower might have safely landed at Pu’uhonua – and maybe that’s why the plants there grow so abundantly today.

Curious to know more about the Place of Refuge? Check out the Pu’uhonua National Historic Site blog.